Birth of the Market Birth of the Market

Information Courtesy of Seattle Municipal Archives

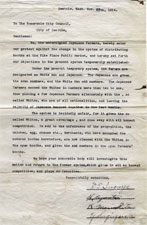

Responding to public outcry over the unreasonably high cost of food and farmer anger about low prices received from commission houses for their crops, the City Council, under the leadership of Council President Thomas Revelle, passed Ordinance no. 16636 establishing a public farmers' market on the west side of Pike Place. The market officially opened on August 17, 1907, and quickly became a popular place for Seattle citizens to shop and save money on food. By 1909, the market averaged 64 farmers per day and 300,000 visitors per month.

Early Expanson Early Expanson

Over the next decade, the City made extensive improvements to the market, including the enlargement of the farmers' stalls area and the construction of arcades, public restrooms and a footbridge to the waterfront. By 1915, the market averaged over 150 farmers per day, with over twice that number in the late summer and fall.

As the owner of the Leland Hotel on the corner of Pike Street and Pike Place, Frank Goodwin immediately recognized the great business opportunity provided by an adjoining public market. He covered the sidewalk in front of his business for the farmers to use. Over the next ten years, his corporation, the Public Market and Department Store Company, bought most of the property surrounding Pike Place and built several private market buildings, including the Corner Market, Economy Market, Sanitary Public Market, and Main Market.

Traffic and the Fate of the Market

Despite its use as a market, Pike Place remained a vital arterial for traffic into downtown and became even more important by 1921 with the extension of Elliott Avenue. Waterfront businesses and the Department of Streets and Sewers demanded that farmers be moved off the street, threatening the existence of the market.

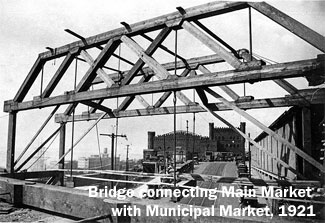

The City Council rejected a proposal to close the market and move farmers to the Westlake Public Market on 5th Avenue between Stewart and Virginia. Instead, they voted to remove the farmers from the street onto the sidewalk, and accepted Goodwin's offer to provide additional space for farmers in a new Public Market building to be constructed across Western Avenue from the Main Market linked by a skybridge.

At first, the farmers were happy with this arrangement because a move to Westlake would have placed them outside of Seattle's then retail core along First and Second Avenues. However, they were soon in conflict with both the City and the Public Market and Department Store Company.

Privatization

As part of its contract, the City gave Goodwin's company the exclusive use of a central section of sidewalk, and allowed them to lease this space as they saw fit. It was assumed that Goodwin would rent this space to farmers or non-competing businesses. Instead, the stalls were leased to the dreaded "middlemen" - competing merchants who sold other farmers' produce including food imported from California.

Amid widespread outcry, Mayor Edwin Brown unsuccessfully proposed tearing down the entire market and replacing it with an even larger market and civic structure that would reach down to the waterfront and cost over $1.5 million. Amid widespread outcry, Mayor Edwin Brown unsuccessfully proposed tearing down the entire market and replacing it with an even larger market and civic structure that would reach down to the waterfront and cost over $1.5 million.

The farmers organized a new group, the Associated Farmers, and chose to sue, contending it was illegal for the City to lease its sidewalks to private businesses. A Superior Court judge ruled that no stalls were legal at all on public sidewalks, farmers' or otherwise. The State Supreme Court overruled that decision, and soon afterwards the City put the issue to rest by vacating the section of sidewalk in question.

The City's Role as Overseer

The City was involved from the beginning in regulating the market. In 1907, the Department of Public Markets and the position of Market Inspector were established, reporting to the Chief of Police. The title of Market Inspector was changed to Market Master in 1912, and the position was transferred to the Health Department. John Winship served as the first Market Inspector/Market Master from 1907 to 1923 and was responsible for issuing permits, assigning tables, collecting rents, receiving complaints and enforcing market rules, including the inspection of farms. The City was involved from the beginning in regulating the market. In 1907, the Department of Public Markets and the position of Market Inspector were established, reporting to the Chief of Police. The title of Market Inspector was changed to Market Master in 1912, and the position was transferred to the Health Department. John Winship served as the first Market Inspector/Market Master from 1907 to 1923 and was responsible for issuing permits, assigning tables, collecting rents, receiving complaints and enforcing market rules, including the inspection of farms.

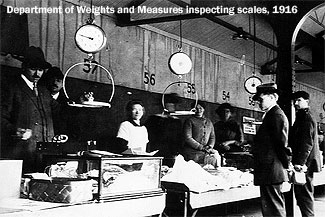

The Health Department regularly inspected food at the market - especially meat, milk and other perishable goods - and ran the Municipal Fish Market from 1917 to 1923. The Weights and Measures Division of the Department of Public Utilities monitored the accuracy of scales, and the Lighting Department provided free lighting and electricity.

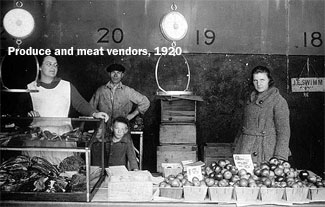

Farmers and the Market

Farmers came from all over the surrounding region. To receive a permit to sell at the market, they were required to prove that their produce was grown on property either leased or owned by them, and that they also lived on this land. Stalls were assigned by lottery; in 1912 rent was 10 cents per day. Farmers came from all over the surrounding region. To receive a permit to sell at the market, they were required to prove that their produce was grown on property either leased or owned by them, and that they also lived on this land. Stalls were assigned by lottery; in 1912 rent was 10 cents per day.

Given the competition for space, there were always complaints about favoritism by the Market Master or cheating by other farmers. In the 1910s, two farmers' associations sprang up: the Washington Farmers Association representing Japanese farmers, and White Home Growers Association representing the rest, including European immigrant farmers. Although these associations sometimes cooperated on areas of common interest, tensions emerged.

Japanese Farmers and Race Relations

Japanese immigrant farmers brought expertise in small plot farming and through industriousness were often able to charge lower prices for their produce. Given the racial sensibilities of the time and the fierce competition between farmers at the market, there were numerous movements in the early days to remove or restrict the Japanese farmers. Official complaints were often couched in patriotism (asserting that only native born citizens should be allowed to sell their goods) or fairness (accusing many of the Japanese of cheating by being 'dummy' tenants and selling produce from other farms). Japanese immigrant farmers brought expertise in small plot farming and through industriousness were often able to charge lower prices for their produce. Given the racial sensibilities of the time and the fierce competition between farmers at the market, there were numerous movements in the early days to remove or restrict the Japanese farmers. Official complaints were often couched in patriotism (asserting that only native born citizens should be allowed to sell their goods) or fairness (accusing many of the Japanese of cheating by being 'dummy' tenants and selling produce from other farms).

The City Council introduced a resolution in 1910 forbidding non-citizen farmers at the market, but opposition from the Chamber of Commerce and a threatened legal challenge from the Japanese consulate prevented its passage. Instead, the lottery assigning stalls was changed so that odd-numbered stalls were assigned to Japanese farmers and even-numbered stalls assigned to everyone else. This pushed many Japanese to the least desirable area in the back of the market.

Pressure to remove or lessen the Japanese presence persisted in the 1920s, through demands for the creation of the Westlake "whites only" farmers market, or by trying to ban produce grown in greenhouses. The Japanese continued to make up the majority of farmers at the market until their removal and internment during World War II.

The Aging of the Market The Aging of the Market

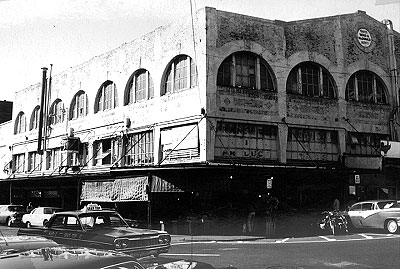

After World War II, the advent of the supermarket, the movement of Seattle's population into the suburbs, and the decline of local truck farms combined to make the Market's role for consumers became less central. The aging Market buildings did little to entice many people away from brightly-lit grocery store aisles. Paint was peeling, walls were cracking, and a general lack of maintenance gave the Market an old and neglected appearance. The number of transients in the neighborhood also served as a deterrent to many shoppers. To some in the community, the Market began looking more and more like an eyesore.

Plans for Change Plans for Change

The first suggestion of impending change for the Market came in 1950, when engineer Harlan Edwards recommended demolishing it in favor of a large parking garage. While this idea went nowhere, in 1963 the business-oriented Central Association of Seattle put forward a proposal that would replace the Market with high-rise office and hotel buildings, as well as a 7-story parking garage. This plan would use federal urban renewal funds and had the support of the Mayor and City Council.

Citizen Protests

Citizens who felt the Market was a unique and valuable resource for the community founded a group called Friends of the Market to fight against the urban renewal plan. Architect Victor Steinbrueck was highly visible in opposition to the Market's demolition, speaking at public meetings and leading protest rallies. Artist Mark Tobey was another prominent Market supporter. Despite the popular uprising against the project, on August 4, 1969, the City Council voted to go ahead with the urban renewal plan. Citizens who felt the Market was a unique and valuable resource for the community founded a group called Friends of the Market to fight against the urban renewal plan. Architect Victor Steinbrueck was highly visible in opposition to the Market's demolition, speaking at public meetings and leading protest rallies. Artist Mark Tobey was another prominent Market supporter. Despite the popular uprising against the project, on August 4, 1969, the City Council voted to go ahead with the urban renewal plan.

Initiative 1

In 1971, Friends of the Market sponsored Initiative 1, which would establish a 7-acre historic district around the Market and a commission to approve and oversee any alteration or demolition of Market buildings. Twenty-five thousand signatures were collected in three weeks to qualify the measure for the ballot that November. The Mayor, City Council, and business community promoted a weaker counterproposal that included a smaller preservation area and less rigorous enforcement. While both groups claimed to be "saving" the Market, the voters preferred the vision of the Friends by a 3-to-2 margin.

Rehabilitating the Market

The Pike Place Market Historical Commission was established by the initiative in 1971 and began meeting immediately. They discussed design guidelines and considered applications for architectural modifications in the Market. In 1973, the Pike Place Market Public Development Authority was created to manage the Market's public buildings. Meanwhile, a large-scale rehabilitation of the Market buildings began in 1975. Community members held a "paint-in" to decorate the walls around the site while the extensive construction was in progress.

The Market Revitalized The Market Revitalized

The ten-year project to restore and redevelop the Market used tens of millions in public and private funds, and proved successful in restoring the Market to a central place in the life of the city. Today the market is the oldest continuously operating public market in the United States, as well as the most historically authentic, and is Seattle's most popular tourist attraction. Meanwhile, the city park near the Market was named for Victor Steinbrueck in 1985 in recognition of his efforts to save this unique Seattle landmark. |